Get Your Ass Behind You

and the art of slingshot making

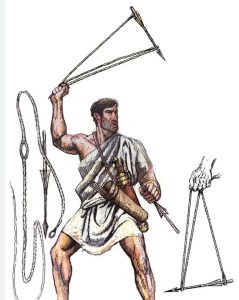

Slingshots go back centuries, of course, as tools of war and to reconcile misunderstandings between neighbors.

What I had in mind was a somewhat more modern variety for shooting at stray dogs, bullfrogs, and tin cans on fence posts.

The following is the tried-and-true method for making a slingshot that I learned that day. It is not the only way, but based on having made a few dozen of them, this is the best method I know of. For those about to embark on their first one, it would be wise not to attempt to “reinvent the wheel” but rather to take Newton’s advice to stand on the shoulders of some giants. If, after making and using a few slingshots by this method, a better way comes to mind, then by all means go for it.

Gathering The Materials

- The Handle

- It should be in the classic “Y” shape. Such branches are generally not found in hardwoods, like Oak. Instead, we look for Willows, growing next to lakes and rivers. Birch and Poplar also grow this way, but Willow is a better choice because of its tensile strength, bending moment, and durability.

- The length of the handle should be one and a half times the size of your hand, so you can grip it below the crotch to avoid hitting your hand with the rock when you shoot.

- The two prongs should be equal in diameter and roughly the same length as the handle, so the wrist of our forward hand can bear the angular force with bands fully extended.

- The Bands

- Natural latex rubber is best because it has a really good modulus of elasticity (look up Young’s Modulus and Hook’s Law), so if you have access to some surgical tubing, get two pieces, each 2 to 3 ft long.

- Really big rubber bands will work, but they will not last as long because of the cheap synthetic material used in making them.

- Otherwise, an old bicycle inner tube will work.

- The Pocket

- Leather is good, but shoe leather is too thick and stiff.

- A piece cut from a welder’s jacket would be a good choice, or some stores carry it for craft making.

- Canvas is an excellent option – like an old tennis shoe (aka sneaker).

- Holding It Together

- Carpenter’s string from the hardware store will work, but it will not last very long.

- Stranded Copper wire from an old extension cord will work.

- Nylon fishing line is best, and it can be found where trees have fallen into the water in lakes and rivers. When fishermen cast too close to the tree, they often have to cut their line to get free.

The Final Assembly

- The Bands

- Measure the distance from your nose to your thumb. That is the length of each of the bands when fully stretched.

- If they are made from an inner tube, make them 1/2 inch wide. Cut with sharp scissors, not a knife – even a razor blade will not work as well as scissors.

- The Handle

- The bark of the Willow branch can be removed or left intact if the branch is green.

- Removing the bark of a green branch will leave a slimy, sticky layer underneath (cambium and phloem). That should be removed by washing it in The Lake with a little scrubbing with beach sand.

- Saw the branch into a comfortable size – 4 to 6 inches for the handle and similar for the prongs.

- Carve a 1/8 inch deep groove, as wide as the bands, near the top of each prong. This is where the bands will connect.

- The Pocket

- Cut the leather or canvas pocket to 2 by 4 inches.

- This is a suitable size for stones under one inch, and marbles, including “steelys”[i]Available from any junkyard from discarded ball bearings, and “boulders”.

- Fold 1/2 inch over on either end and cut a slit through both folded layers with a sharp knife on both ends.

- Slip one inch of each band through the slits in the pocket.

- This final step requires a second person.

- The first person holds the pocket in one hand and stretches the folded end of one of the bands with the other, using pliers.

- The second person ties the fishing line around the band, where it attaches to the pocket.

- The process is repeated with the handle in one hand while gripping the folded bands with pliers.

- The bands are stretched as much as possible while the other person ties them tightly.

To read about Slingshots, click the page divider above.

The point of the slingshot story is that Dad had probably not made one since the 1920s, and even though the ensuing three decades had changed technology in many ways, he kept an open mind, and “kept his ass behind him”. His ability to think clearly about each step, considering all the possibilities along with what he had known from past experience, allowed him to stick with certain “old” time-tested ideas that were still better than the “new” ones.

It is not necessary to reinvent things simply because they are based on old ideas, or because we don’t understand them. When we encounter unfamiliar things or things that seem out of place, it’s always a good idea to consider that there are likely good reasons not to change them, wiithout first gaining a full understanding of what has gone before. It can be a good reminder that neither “New” nor “Different” is a synonym for “Improved”.

By: Jim

Written: December 2025

Published: December 24, 2025

Revised:

Revised:

footnotes

| ↑i | Available from any junkyard from discarded ball bearings |

|---|